(Disclaimer: I’m not a front-end guy nor am I a designer. I dabbled in some HTML and CSS in my early days but I’ve majorly been a back-end guy for most of my career. However, I’ve always wanted to build something interesting and appealing from the ground up that involved at least some basic design. Here goes its story…)

TL;DR: Built a word game in Java using JavaFX, the code for which you can find here. If you are just interested in playing the game, download the latest artefact here. Note that you need to have Java 8 installed on your machine to play the game.

One of my favorite ways to tackle boredom, like most people of my age, was to play mobile games for hours on end until the rush of playing would finally subside and I had to search for something else to do. Wordament, the word game published by Microsoft Studios was one such game for me.

The basic idea of Wordament is you’re given a 4x4 grid of English alphabets and you need to make as many words as you can by traversing through the letters in some fixed time. The game also had different variations to the basic idea in each round to make it interesting for the players. I often found myself spending more than a couple of hours some evenings trying to get better at the game with each passing round. It was challenging to get above the 90 percentile mark, but it was also immensely fun and once you start playing it, you’ll realize why the game is so popular among netizens.

Anyway, it was during one of those ‘gaming sessions’ that I started to think if it was a good idea to try and develop such a word game of my own. Of course, my idea wasn’t to build something much different from Wordament. In fact, I liked the game so much that I wanted to build something unambiguously similar to it and see how I would fare. I could, of course, use my discretion to implement the features and design, so that was that and not to mention how much fun it would be to build something like that from scratch. I certainly had enough incentive to start coding.

After giving it some more thought, I got down to the basic idea of what I wanted to build and how I was going to do it. As I said, it wasn’t supposed to be much different from Wordament — the user should be able to make words out of a 4x4 grid of letters with some sort of time control; that was going to be core idea of the game.

At the time of writing this game, my preferred language was Java. Some research on the web told me that JavaFX is great for building GUIs in Java. JavaFX has even replaced Swing as the recommended GUI toolkit for Java. Furthermore, JavaFX is more consistent in its design than Swing, and also has more features. It is more modern too, enabling you to design GUIs using XML-based layout files and style them with CSS, just like we are used to with web applications. JavaFX also integrates 2D + 3D graphics, charts, audio, video, and embedded web applications into one coherent GUI toolkit. Based on what I read, it was clear to me that JavaFX was the way to go.

JavaFX allows users to configure the different GUI components in your application through FXML, an XML-based interface markup language created by Oracle just for this purpose. Before you start to get all jittery about working with XML, fortunately, there’s some good news too. JavaFX also comes with what is called the SceneBuilder which makes hooking in the various GUI components into your application quite seamless. SceneBuilder helps you do away with working with any FXML while developing your application by translating your changes into FXML by itself, which is pretty nifty to say the least.

Once I decided what tools I was going to use to build my game, the next task was the interesting part — to start coding!

Before I started writing code, there were a few design considerations I had to think about and conclude on so that I could enjoy a more systematic workflow towards building the game. Some of them are:

Only after I concluded on these design decisions was when I got down to the actual implementation.

The first part of my implementation was writing code to read all the dictionary words from a file and save them into a Trie when the app first starts up. But before that, I had to get hold of a good quality dictionary in file format that I could use for this purpose. It took me a bit of searching around to find one that suited my needs and I don’t exactly remember the source, but safe to say I found it in another GitHub repository. The file has more than 370,000 English words which you can find in my repository here.

If you’ve come across the Trie data structure for the first time here, you should definitely read up more on it to understand how it facilitates faster insert and lookup operations in exchange for generous memory requirements. Storing a huge set of strings for exact as well as prefix search is a typical use-case where Trie shines. In my case, it wasn’t any more than a straightforward implementation of the Trie to store and retrieve words, but if you want to take a look at the code, you can find it here.

The next part of the implementation I started working on was building the actual game representation. The initiation of this endeavour was the creation of the Game class along with its accompanying solver both of which, together encapsulate the logical abstraction behind a game. The Game class is responsible for creating the 4x4 grid, populate it with random (or maybe, not so random!) alphabets and use the solver to find all the possible words formed out of the grid. The GameSolver class receives the grid created by its parent Game class and uses the dictionary created as a Trie to solve the 4x4 grid and passes the results back to its parent.

How do you populate the grid of alphabets so there’s a good probability of a high number of words being formed out of the letters? If you think about it, it’s immediately obvious that populating the grid with alphabets in a totally random fashion is of little good; such grids will amount to no more than 20 or so words. So, what then, is a fairly good way to populate the grid?

One straightforward clue to solve the problem is to consider the fact that vowels appear more frequently than consonants in the English vocabulary. So, if you assign a weight to each letter of the English alphabet with the intention of achieving a higher total score for all the words in the dictionary, you’d want to assign more weight to the vowels than the consonants. Going by this argument, I decided to implement such a weighted ordering on all the letters where the vowels have a higher number for that value than the consonants. I concluded on the final weights of the letters by applying a simple heuristic of matching the value with the frequency of alphabets in the vocabulary. The higher the frequency of a particular letter in the vocabulary, the higher its weight. With this logic in place, I only had to pick a random letter once from this weighted list of alphabets 16 different times to populate the entire grid with letters.

Here’s the relevant snippet of code from the Alphabet class:

public enum Alphabet {

A(20, 1),

B(10, 3),

C(12, 3),

D(12, 2),

E(10, 1),

F(10, 4),

G(10, 2),

H(15, 4),

I(20, 1),

J(5, 8),

K(5, 5),

L(12, 1),

M(12, 3),

N(15, 1),

O(20, 1),

P(10, 3),

Q(2, 10),

R(15, 1),

S(15, 1),

T(20, 1),

U(12, 1),

V(5, 4),

W(10, 4),

X(2, 8),

Y(10, 4),

Z(2, 10);

private static int totalWeight = 0;

static {

for (Alphabet alphabet : values()) {

totalWeight += alphabet.getWeight();

}

}

private int weight;

private int score;

Alphabet(int weight, int score) {

this.weight = weight;

this.score = score;

}

public static Alphabet newRandom() {

int value = 1 + ThreadLocalRandom.current().nextInt(totalWeight);

for (Alphabet alphabet : values()) {

value = value - alphabet.getWeight();

if (value <= 0) {

return alphabet;

}

}

return null;

}

}

The newRandom() method defines the logic to fetch a random alphabet in accordance with the weight assigned to each of the letters. I just make a call to this method each of the 16 times to populate the complete grid and we now have a much higher chance of creating a game with a good number of words in it.

As you see in the code snippet above, along with the weight, each letter is also assigned a points value that indicates the score attached to it. When the user makes a particular word in a grid, he is awarded the score that is cumulative of the points of all the letters in that word. Naturally, the higher the weight of a letter, the lower its points.

Now, given a way to fetch a random alphabet according to the assigned weights, it’s up to the Game class to use this logic to populate its grid.

private void populateGrid() {

for (int i = 0; i < 4; ++i) {

for (int j = 0; j < 4; ++j) {

grid[i][j] = new GridUnit(Alphabet.newRandom(), new GridPoint(i, j));

}

}

}

The next part of the implementation phase was writing the GameSolver class to crawl the 4x4 grid of letters to find all the possible words in a given game. The idea is to recursively traverse the entire grid and check if the given chain of letters form a valid word. I also do a prefix check of the word in the Trie to see if I need to proceed further with the chain. If there’s no word in the dictionary that starts with the current chain of letters, I just backtrack to pursue the other chain of letters. Here’s the relevant snippet of the GameSolver class:

public GameResult solve() {

for (int i = 0; i < 4; ++i) {

for (int j = 0; j < 4; ++j) {

boolean[][] visited = new boolean[4][4];

for (boolean[] row : visited) {

Arrays.fill(row, false);

}

GridPoint point = grid[i][j].getPoint();

this.crawl(point, "", new LinkedList<>(), visited);

}

}

result.defineQuality();

return result;

}

private void crawl(GridPoint point, String prefix, List<GridPoint> seq, boolean[][] visited) {

GridUnit unit = grid[point.x][point.y];

visited[point.x][point.y] = true;

String word = prefix + unit.getLetter();

if (this.dictionary.prefix(word)) {

seq.add(point);

int score = this.validate(word);

if (score > 0) {

this.result.put(word, score, seq);

}

for (GridPoint n : point.getNeighbors()) {

if (!visited[n.x][n.y]) {

boolean[][] v = Utils.arrCopy(visited);

this.crawl(n, word, new LinkedList<>(seq), v);

}

}

}

}

The full source code of the solver can be found here.

The GridPoint that you see in the above snippet represents a single unit of the grid which is, by all means, a traditional plain-old-java-object that has the row and column of the given grid cell along with a method to compute its neighboring cells. As you can see in the code section below, each grid point can have a maximum of 8 neighbors, which means we need to only consider a maximum of 8 surrounding grid points for each grid point while traversing the grid to form words out of the letters.

public GridPoint(int x, int y) {

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

}

private List<GridPoint> computeNeighbors() {

int[] dx = {-1, -1, -1, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1};

int[] dy = {-1, 0, 1, -1, 1, -1, 0, 1};

List<GridPoint> neighbors = new ArrayList<>(8);

for (int i = 0; i < dx.length; ++i) {

GridPoint n = new GridPoint(this.x + dx[i], this.y + dy[i]);

if (n.isValid()) {

neighbors.add(n);

}

}

return neighbors;

}

The exact purpose of keeping track of this sequence of GridPoints for each word in the grid is something that we will come back to later.

One of the design considerations I mentioned earlier was to make sure a fixed number of games are present in the background at all times so that there’s no overhead in popping a new game for the user when necessary. This job is accomplished by the GameFactory class.

This game factory is instantiated when the app first starts up along with loading the dictionary words into the Trie. Once instantiated, a LinkedBlockingDeque of Game objects is created along with an executor of fixed size. The latter then creates the initial set of games and pushes them into the queue. Additionally, whenever an existing game is popped from the queue and presented to the user, another game is immediately created and pushed into the queue by the executor thereby ensuring that a certain number of games are always present in the queue. This way, if the user, for some reason, wants to create new games in quick succession, the app has enough room before it starts to block on the UI.

You can look at the implementation here.

Earlier, I also mentioned about assigning a notion of quality to the games created by the executor. Let’s talk a bit more about it now. The notion of game quality is important because we don’t want to show games that have very few words to the user. To keep it simple, I decide the quality of a given game based on just the number of valid words formed from its grid. You could tune it a little more by also taking into consideration the total score or the average length of words, but overall, it doesn’t matter much. Because of how we’re populating the grid, a higher number of words in the grid generally translates to proportionally higher numbers for other parameters too.

A newly created game can have one of these three qualities assigned to it: LOW, MEDIUM and HIGH. Each of the qualities have a certain threshold value that specifies the minimum number of words a game should have to claim that quality. While a game with LOW quality is discarded by the executor immediately after it’s created, there’s a subtle difference between the MEDIUM and HIGH quality games.

A game with MEDIUM quality is considered to be a good game, except that it’s pushed to the tail end of the queue while a HIGH quality game is pushed to the head of the queue. This way, the user is guaranteed to see a game with high number of words before the ones with lesser number of words whenever possible.

After having written code for the ideas discussed so far, it was finally time to take the plunge and address the beast.

Don’t get me wrong — I say front-end is a beast not because it’s any more difficult or different from writing code that’s not front-end, but because I’ve done very little front-end work myself. However, contrary to my expectations, JavaFX made my journey fairly easy and joyful and I’d like to talk about it in this section.

There are many excellent tutorials out there that help you get started with JavaFX, so I’m not going to get into much details here and only briefly talk about it to give you a basic overview of the platform before I delve into some of the internals of the game.

The core logical abstraction behind building GUIs using JavaFX are the stage and scene . A stage represents any open window in a JavaFX application which is capable of displaying content inside it, referred to as the scene. A scene is essentially a collection of GUI widgets that together make up an interactive component of your application. It’s common, imperative even, to nest your widgets within one another in a structured manner to produce a well-defined view in the scene. This hierarchical tree of nodes that represents all of the visual elements of your application’s user interface is called the scene graph.

Inside the same stage, you can conveniently swap scenes, each with its own scene graph, to show content that keeps changing, but you are allowed to display only one scene in the stage at any given time. Of course, you can have multiple GUI components in the same scene, so there’s always a way to show loaded content inside the stage within a single scene.

When a JavaFX application starts up, a root stage is created by itself which represents the primary window of your app. For simpler applications, you only work with this primary window, but for even slightly complex applications, you often create additional stages whenever you need to open more windows.

JavaFX allows you to configure the GUI elements in your application using either the native FXML or better even, with a tool called the SceneBuilder. The SceneBuilder conveniently allows you to drag-and-drop your choice of widgets into the scene and translates the changes into FXML files that are required to display the user interface of your application.

Just want to add a note here about using SceneBuilder — I’ve used the default SceneBuilder that comes with the IntelliJ editor and it works just fine most of the time, but there are a few glitches that appear from time to time. The best way to get around this problem is to work with a separate standalone installer from Gluon which you can find here. Use Gluon’s SceneBuilder to create your scene graph, copy the translated FXML files to the workspace in your favorite editor and work with them. It’s a hassle, but it works.

JavaFX comes with a wide range of GUI widgets/nodes that you can show in your scenes. Some of them are containers like the AnchorPane, BorderPane, GridPane or the VBox which are capable of housing other widgets. Then, you have control widgets like the ImageView, ListView and the Button. These control widgets have to be placed inside a container widget to be rendered in the scene. Then, there are also the Menu controls, Shapes, Charts and the 3D widgets, all of which can be part of your scene graph depending on the view you want for your application.

Typically, every logical component in your scene graph is represented by an FXML file and a corresponding Controller class. While the FXML file controls the layout and styling of the individual widgets in your component, the controller allows you to implement the business logic of your component by defining the various event-handlers for your widgets. For instance, when you create a menu-bar component, the corresponding FXML file has the details of the various menu items along with their layout and CSS while the controller defines what happens when you click on the menu items. Note that you can define only one Controller class per FXML document. That is to say, a logical GUI component should be represented by a single FXML-Controller pair. Not more, not less.

The suggested way of building the visual components in your JavaFX application is by defining the smallest individual components that can be isolated into separate FXML-Controller pairs. These individual components can contain any number of nodes in total, but only a single root container node that has other nodes as its children in a hierarchical fashion. All the nodes together constitute a single meaningful visual entity in your application. That way, it becomes really easy to create your scenes by hooking in the components or even simply re-use them wherever possible. Creating a new component is as simple as loading the corresponding FXML.

Till now, we’ve only talked about JavaFX in general. I’ll now talk a bit about the most important scene in my app, the game scene. This will hopefully give you more insight into building the visual elements in your own application.

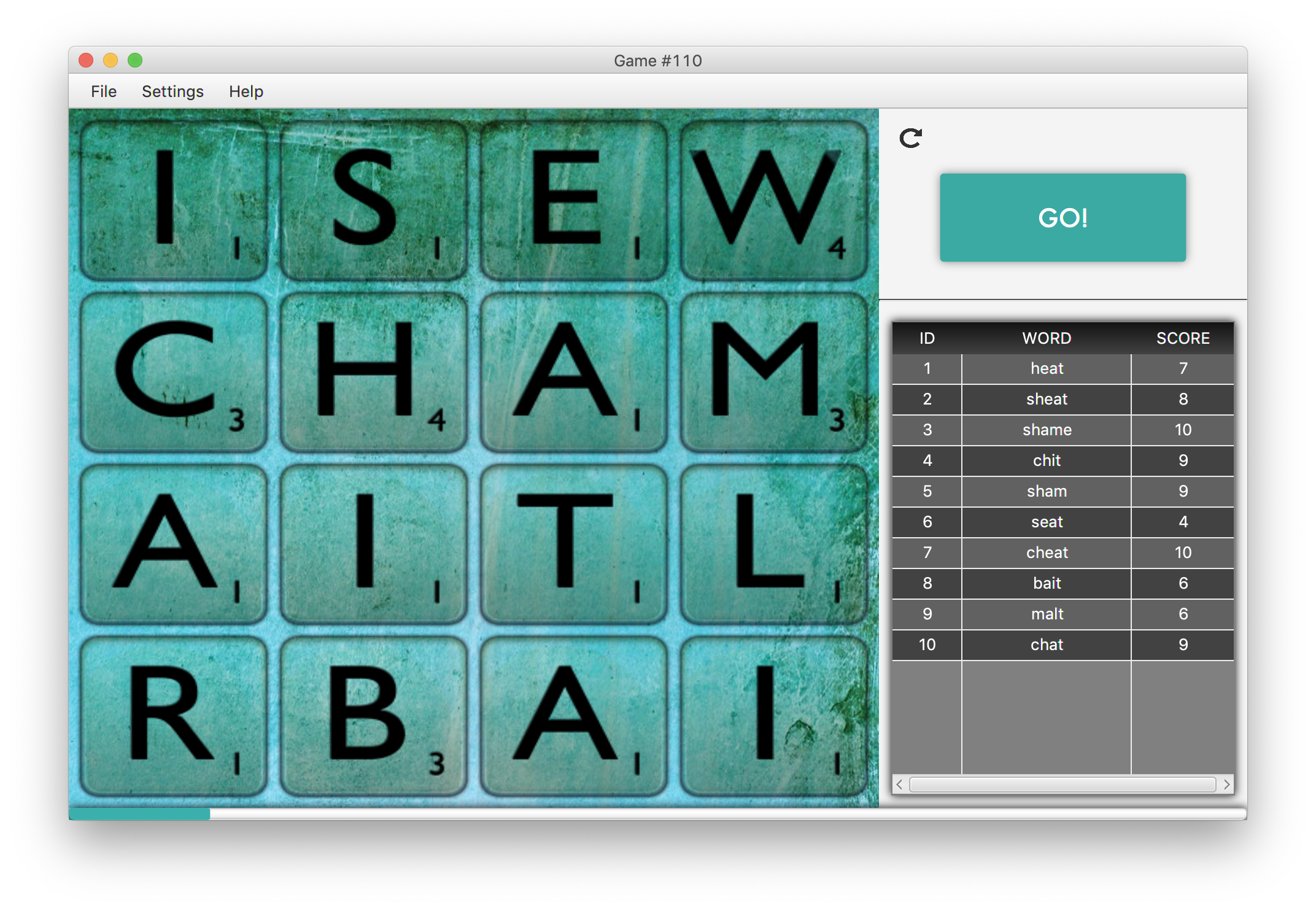

The game scene is the scene that is displayed inside the primary stage when the user asks to play a new game. As noted earlier, a scene in JavaFX comprises of multiple GUI components which in turn comprise of multiple nodes/widgets, all contained within a single parent node. The game scene is no different.

In the image above which represents the game scene from a certain game, you can see that there are multiple widgets. On the left there’s the GridPane with the 4x4 grid of letters. This grid pane in turn has 16 Pane widgets inside it, each of which has an ImageView that contains the image of the alphabet assigned to it. On the right is a VBox that contains the following widgets:

ImageView — contains the rotate icon which when clicked will rotate the GridPane on the left once by 90 degrees.Button — the button the user clicks to submit a word.SeparatorTableView — table that is continuously populated with the words made by the user.AnchorPane — the container for the table.At the bottom of the scene is the ProgressBar that indicates time elapsed/left in the game.

The parent node for all these child nodes is the BorderPane widget.

As you can see, there are a good number of nodes in the scene graph of this game scene. However the scene has only 4 logical components — GameGridComponent, GameResultComponent, ProgressBarComponent, MenuBarComponent, each of which has a fraction of nodes that belong to the scene. That means each of these components has a separate FXML-Controller pair and all the components co-ordinate among themselves via their Controllers and together constitute the game scene.

It’s common to have the controllers in your application share each other’s instances and data among themselves to produce a working scene. For instance, in my game, the GameResultComponent is provided with the GameGridComponent because the former contains the rotate ImageView, which when clicked, should rotate the grid that belongs to the GameGridComponent. Such a design is a recurring theme while working with JavaFX and is perfectly acceptable.

In general, once you decide which nodes you want to have in your scene graph, the next step should be to understand the interaction between each of these nodes.

The two most important points you’d want to address when building your scenes are:

Once you have that, it’s easier to figure out how to separate them into different entities and facilitate their interaction. Again, to re-iterate, each of these components is essentially an FXML-Controller pair. The FXML file allows you to layout the various nodes of the component among each other and style them with CSS while the Controller allows you to specify the business logic of your widgets.

I’ll be honest here — I like the look of the game more than I probably should, it’s embarrassing. But I’m glad I’ve managed to make it look the way it does with my rather limited experience and design sense. However, credit needs to be given where it’s due — JavaFX does pretty well here, especially with its animations and I didn’t have to do much to achieve the style you see in my game.

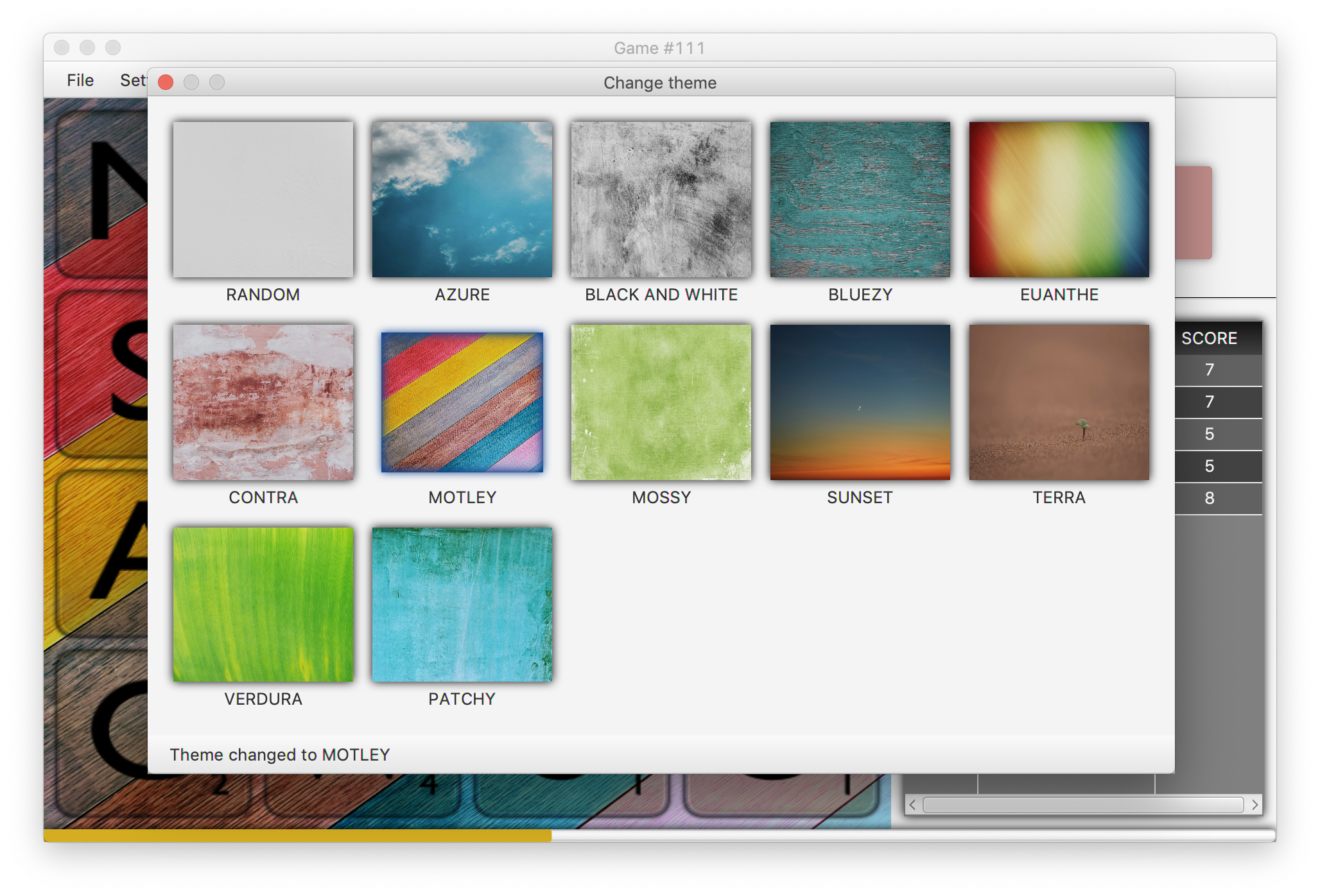

Themes is a little fun thing I decided to have in my game, just because, well, who doesn’t like playing with themes every now and then?

As you can see in the image above which represents the ChangeThemeScene , there a multiple themes that the user can choose from. Each theme has an image and a CSS file associated with it. While the image appears as a background for the game grid, the CSS file adds theme-specific style to the other style-able components of the scene. This is made possible by registering the root node of the game scene with the theme-change event-handler. Whenever the theme is changed in the ChangeThemeScene, a theme-change event is triggered which is dispatched to the root node’s event-handler. The root node then clears its current stylesheets list and adds the new theme to this listenable list. JavaFX does the rest and the new style is immediately reflected. Here’s the relevant code snippet from the FxScene class:

private void applyCurrentTheme() {

String styleSheet = this.loadTheme().getStyleSheet();

this.root.getStylesheets().clear();

this.root.getStylesheets().add(styleSheet);

}

protected void setEventHandlers() {

this.root.addEventHandler(

Theme.ChangeEvent.THEME_CHANGE_EVENT_TYPE,

(event -> {

this.applyCurrentTheme();

event.consume();

}));

}

Here’s the motley.css file that is set as the root node’s stylesheet when the theme is changed to MOTLEY as shown in the above image:

@import url("common.css");

.custom-button {

-fx-text-fill: #000000;

-fx-background-color: #C18D8A;

}

.custom-button:hover {

-fx-background-color: #AB7676;

-fx-cursor: HAND;

}

.custom-button:pressed {

-fx-background-color: #A96150;

}

#gamePane {

-fx-background-image: url("../files/motley.jpg");

}

.progress-bar .bar {

-fx-background-color: #D4AD20;

-fx-background-insets: 0, 1, 2;

-fx-padding: 0.416667em;

}

.text-field {

-fx-background-color: #C18D8A;

-fx-text-fill: #FFFFFF;

}

You can check out more tidbits of styling in the game by trying it out here.

JavaFX has very good support for animations. In JavaFX, a node can be animated by changing its property over time. The javafx.animation package comes with a wide range of transitions such as the RotateTransition , FadeTransition , ScaleTransition , StrokeTransition and many more. Depending on how you want your nodes to look, you can apply any of these transitions and even different combinations of them wherever you want to and create the styles you wish to have in your app.

For instance, the video below demonstrates how the RotateTransition is applied to the ImageView controls when the user submits a valid word in the game.

Remember how I was keeping track of the GridPoint objects for each valid word while solving the grid in the GameSolver class? This sequence of grid points is used to apply the appropriate styling to the ImageView nodes contained at those grid points when the user clicks on the ‘GO!’ button. Check the code snippet below from the GamePlayStyler class where the RotateTransition is applied to the nodes that form a valid word in the grid.

private void applyRotateTransition() {

this.seq.forEach(this::rotate);

}

private void rotate(ImageView imgView) {

RotateTransition transition = new RotateTransition(Duration.millis(65), imgView);

transition.setByAngle(360);

transition.setCycleCount(4);

transition.play();

}

Similarly, the FadeTransition is applied to the nodes when the user submits an invalid word. Check the video below.

When the user submits a word that’s already been submitted, the ScaleTransition is applied to the cells as demonstrated in the video below.

It’s also possible to rotate the game grid by 90 degrees by clicking on the rotate icon on the top right of the window. This offers a different perspective of the letters in the grid to the user resulting in a possibly better chance of finding new words.

Again, this is also a RotateTransition that’s applied to the game grid this time, but that’s not all. It’s not as straightforward as simply rotating the grid by 90 degrees and the individual ImageView nodes accordingly. That would do nothing but interchange the axes and cause the grid to violate the bounds of the stage. What I do here, instead, is rotate the GridPane by 360 degrees and also apply a RotateTransition on the individual nodes by 90 degrees with a cycle count of 2, but all that’s just an illusion of actually rotating the game pane. It doesn’t actually do anything to rotate the grid, rather only produce a presumably interesting animation and trick the user into thinking that the grid has indeed been rotated. The actual rotation is done by manually rearranging the ImageView nodes as they should be had the transition been applied as expected.

private void rotateGrid() {

for (int x = 0; x < 2; x++) {

for (int y = x; y < 3 - x; y++) {

Pane temp = this.panes[y][3 - x];

this.panes[y][3 - x] = this.panes[x][y];

this.panes[x][y] = this.panes[3 - y][x];

this.panes[3 - y][x] = this.panes[3 - x][3 - y];

this.panes[3 - x][3 - y] = temp;

}

}

for (int i = 0; i < 4; ++i) {

for (int j = 0; j < 4; ++j) {

Pane pane = this.panes[i][j];

GridPane.setRowIndex(pane, i);

GridPane.setColumnIndex(pane, j);

}

}

}

The above code snippet shows the logic applied to rearrange the Pane nodes containing the ImageViews in the GridPane. This logic along with the combination of transitions applied on the nodes as described above produces the desirable effect of rotating the grid by 90 degrees along with a somewhat interesting animation on the cells as well, as shown in the video below.

As you can see, you can achieve interesting animations in your JavaFX application by combining multiple transitions applied to different nodes. The SequentialTransition and ParallelTransition animations are particularly useful in such a scenario as they allow you to club animations and run them together in different ways.

The following code snippet shows the transitions applied to the GridPane and its children ImageView nodes as discussed above.

private SequentialTransition sequencer = new SequentialTransition();

private void rotateGamePane() {

RotateTransition gridTransition = new RotateTransition(Duration.millis(75), this.gamePane);

gridTransition.setByAngle(360);

gridTransition.setCycleCount(1);

this.sequencer.getChildren().add(gridTransition);

imgViews.forEach(

imgView -> {

RotateTransition imgViewTransition = new RotateTransition(Duration.millis(20), imgView);

imgViewTransition.setByAngle(90);

imgViewTransition.setCycleCount(2);

imgViewTransition.setAutoReverse(true);

this.sequencer.getChildren().add(imgViewTransition);

});

this.sequencer.play();

this.sequencer.setOnFinished(

event -> {

this.sequencer.getChildren().clear();

});

}

You can find more code related to animations in my game in the GamePlayStyler class.

All in all, I really enjoyed writing my first front-end heavy app using JavaFX. I know it’s not much, but I liked writing it nonetheless. JavaFX is pretty nifty and even though still under development, it certainly packs a punch and gives you enough features to develop rich desktop applications seamlessly.

If you like how my game looks and want to give it a try, you know where to go. If you are interested in reading the code, here’s the link to the GitHub repository. I certainly don’t mind if you want to give it a star; just letting you know ;)

So, that’s pretty much it. Feel free to comment if you want more details or just want to give some feedback. If you are interested in contributing to the game, file a pull request or shoot a mail to me. You can find my e-mail ID on my GitHub profile.

Thanks for reading! Hope you got something out of it. Happy coding to y’all, and cheers!